A recurring theme in Medieval aesthetics is the relationship between microcosm and macrocosm. What fascinated the medievals about this relationship was the idea of order which was identified with the beautiful. This aesthetic ideal of beauty was thought to be present in creation, which is ordered and harmonious. Not only was the universe considered beautiful in its own right because of its orderliness, but it was also valued by the medievals because it was “God’s handiwork.” The world was a means of perceiving the order and beauty of God, and its order was viewed as something which the human being should imitate. The popularity of this cosmic vision cannot be overstated; “there was not a single medieval writer who did not turn to this theme of the polyphony of the universe.” The concept of an ordered cosmos, from its smallest to its largest aspects pervaded the art of the time, from stained glass to manuscript miniatures, to the great Gothic cathedrals.

This cosmic vision, which sought to harmonize all things, was a part of the Medieval spirit in general. Every aspect of Medieval culture was imbued with the spirit of systematization. It was this desire to systematize that led to their cohesive cosmic vision. The Medieval period was essentially a manuscript culture and formed its body of knowledge based on the writers of the past. In gathering and organizing information, they built a system of knowledge which was able to create unity among variety. Not only did the result of this organized body of knowledge, informed by Greek thought, inform their vision of the world, it was also itself a symbol of this vision. C.S. Lewis called this cosmic “Model of the Universe” their “supreme work of art.” It was, he said, “the central work…in which most particular works were embedded.”

The wider culture was informed by this vision not only in the realm of art, but also in societal organization such as in its plan of the university and the feudal structure of society. These organizations imitated a cosmic vision not only in their complex integration of the whole, but also in their hierarchical structures. The interconnectedness of their systems was “not in flat equality, but in a hierarchical ladder.” For example, while all of the liberal arts of the university were connected to one another, philosophy and theology were still paramount. In the same way, the order of the universe was hierarchical in addition to its interconnectedness; God is the Supreme Being at the top of the great chain of being, and it is from him that all creation is sustained in its existence, beauty, goodness, order, etc. They are ultimately connected to one another by their relationship to him.

This value on orderliness came into the Middle Ages, through Boethius and St. Augustine, from the philosophers of ancient Greece. The ancient Greek conception of the universe was inherently ordered. Their word kosmos was itself defined as “ordered universe.” But it was Pythagoras who coined the term and concept of the music of the spheres which came to inform Boethius’ considerations of music. Pythagoras explained that the planets each produced their own sound, due to their motion, and that these sounds together created musical harmony in the heavens. While, in fact, this was later shown not to be true, the connection Pythagoras made between music and the heavens illustrates the concept of harmonious order. Boethius, following in Pythagoras’ footsteps, also speaks of cosmic music in his Fundamentals of Music. In this work he describes various types of music: cosmic, human, and instrumental. These first two are more theoretical than experiential. He described cosmic music as “discernible especially in those things which are observed in heaven itself or the combination of elements or the diversity of seasons.” While the innumerable amount of substances contained in the universe would seem to cause chaos, Boethius notes that order is maintained by the higher structures such as the seasons. The world was diverse, but also structured. Like a great ecosystem, all of its parts worked in harmony and none of its components could be removed without ruining the whole; “all things would seem to fall apart and, so to speak, preserve none of their consonance.”

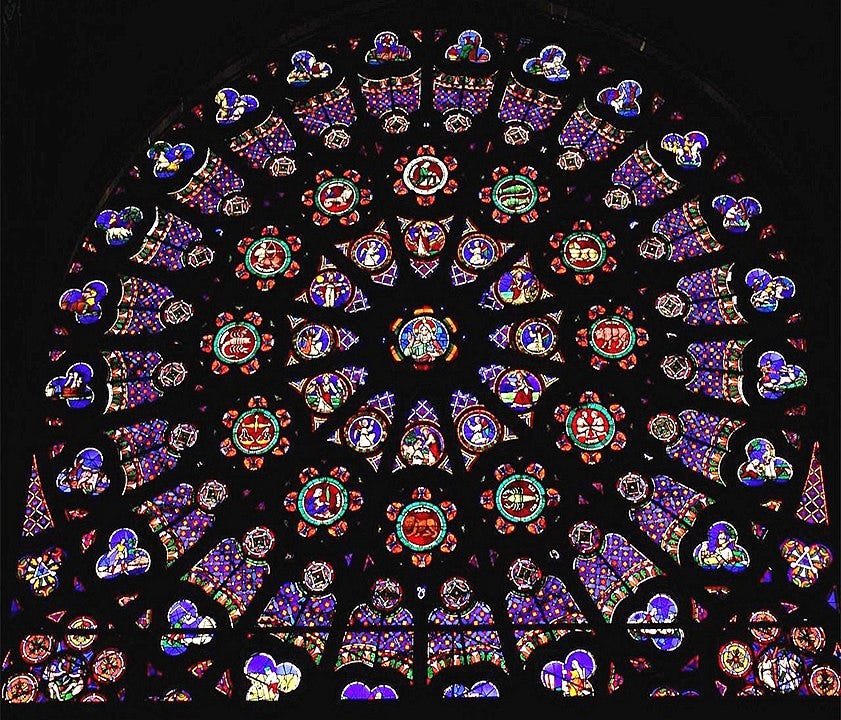

Harmony and order existed, then, not only in the motion of the planets and their ever-regular orbits as in Pythagoras’ music of the spheres, but harmony also existed on earth. This had a great impact on the medieval view of art. Eco relates that the medievals saw “beauty in the cycles of the universe, in the regular movements of time and the seasons, in the...rhythms of nature, the motions and humors of biological life.” Examples of this concept of beauty can be seen in the many rose windows used in Gothic cathedrals which were “born of a cosmic metaphor.” It can also be seen in artworks that depict zodiac signs and the labors of the months.

By meditating on this order of the world, the human being is able to discern the order and beauty of God. For Augustine, such reflection is essential to our relationship with God, and our orientation toward him, for “‘order is that which will lead us to God, if we hold to it during life; and unless we do hold to it during life, we shall not come to God.’” Pondering this order is, for Augustine, a moral requirement because it is a means of obtaining knowledge of God.

Another Medieval philosopher who spoke of the need for human beings to recognize this order of the cosmos was St. Bonaventure. Bonaventure held that the world is “offered to us as a sign inviting us to pass beyond it.” This kind of thinking, that the material was a means of contemplating the immaterial, was a popular theme of the Middle Ages, not only among philosophers and theologians, but also among artists. The Abbot Suger, for example, wrote on the doors of the main entry of St. Denis: “A dull mind rises towards truth through material things; And once seeing this light, it rises above being immersed in them." St. Bonaventure explained that the main way in which we move into contemplation of the immaterial through material things is by perceiving their order. Following St. Augustine, and interpreting a verse from the Book of Wisdom he states that, “the observer considers things in themselves and sees in them weight, number, and measure… [and] from all these considerations the observer can rise[s] to the knowledge of the immense power, wisdom, and goodness of the Creator.” Therefore, the cosmos served as a revelation of God.

While the macrocosm reveals God’s order, so too does the human being. The human being is called, by virtue of his microcosmic structure, to imitate the order of God found in nature. To a certain extent the human being already reflects this orderliness since he is a part of creation. Man stands as a kind of metaphysical mirror of the macrocosm of the universe, he is, as Maximus the Confessor stated, “the 'natural link, everywhere…reducing to a unity things which in nature are widely disparate.’”

However, it was not only his metaphysical place in the universe that united him to the cosmos, but he was also called to imitate the order of it within his own soul. The order of the soul consisted in moral goodness. One means of establishing this order in himself, in addition to virtue, was through music. Here the connection between the third type of music, instrumental music, finds its place in relation to cosmic and human music. For the Greeks, Boethius and other Christian philosophers, certain “musical modes had differing effects upon people.” For example, “a lascivious disposition takes pleasure in more lascivious modes or is often made soft and corrupted upon hearing them.” Instrumental music was able to influence the harmony or disharmony of the human person.

In addition to this, instrumental music was also itself a reflection of the order and harmony of the universe. For instance, polyphony, as John Scotus Eriugena notes, was “‘an organized melody composed of diverse qualities and quantities of voices’” which are “‘co-adapted in accordance with [the] rules of the art of music.” Music served as a kind of metaphor for the cosmos, and the cosmos were often spoken of in musical terms. William of Auvergne, for instance, proclaimed “‘When you consider the order and magnificence of the universe…you will find it to be like a most beautiful canticle…and the wondrous variety of its creatures to be a symphony of joy and harmony to very excess.’”

Medieval aesthetics was grounded in a metaphysical vision of the universe which was systematic and all encompassing. The relationship between microcosm and macrocosm was established by order and found metaphorical expression in music. This characteristic Medieval vision of the whole came to influence all mediums of art in form as well as in its content.

Bibliography

Abbot Suger of St. Denis. Selected Works of Abbot Suger of Saint Denis. Trans. Richard Cusimano. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2018.

Bai, Junxiao. “Numbers: Harmonic Ratios and Beauty in Augustinian Musical Cosmology.” The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy 13, no. 3 (2017): http:// cosmosandhistory.org

Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Fundamentals of Music. Trans. Calvin M. Bower. Ed. Claude V. Palisca. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Bonaventure, The Journey of the Mind to God. Trans. Philotheus Boehner. Ed. Stephen F. Brown. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993.

Bužarovski, Dimitrije. “Generative Ideas in the Aesthetics of Music.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 17, no. 2 (1986): 163–184.

Di Bondone, Giotto. “Scrovegni Chapel,” painting, ca. 1305, http://wikipedia.org.

Dow, Helen J. “The Rose-Window.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 20, no. 3/4 (1957): 248-297.

Eco, Umberto. Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages. trans. Hugh Bredin New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002.

Gilson, Étienne. The Philosophy of Saint Bonaventure. Trans. Illtyd Trethowan and F. J. Sheed. Providence, RI: Cluny, 2020.

Guiu, Adrian. “Eriugena Reads Maximus the Confessor: Christology as Cosmic Theophany.” In A Companion to John Scotus Eriugena. ed. Adrian Guiu, 296-325. Boston: Brill, 2020.

Lewis, C.S. The Discarded Image. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Limbourg Brothers. “March,” Très Riches Heures of Duc De Berry, miniature, ca. 1412-1416, http://wikipedia.org.

“North Rose Window, Basilica of St. Denis,” stained glass, ca. 1135-1144, http://wikipedia.org.

“The Celestial Virgin and Child,” miniature, ca. 1420, http://metmuseum.org.

Von Bingen, Hildegard. “The Universal Man,” miniature, 1165, http://wikipedia.org.